Natasha Silva, 28 years old, lives in a favela in São Paulo, the largest city in Brazil. Mother of three, she was fired from her job as a cleaning assistant, due to COVID-19. In addition to the lack of salary, she faces another drama, the consequence of classes’ suspension is that she needs to pay for all the children’s meals (Folha de São Paulo, 03/27/2020). Luciana dos Santos, 45, also living in a favela in the same city, was already unemployed before the crisis. With the closure of schools, five of her nine children are without receiving the only balanced meal of the day. Luciana has been looking for food in supermarket dumps, without finding it (Folha de São Paulo, 10/04/2020).

By Paulo Cruz Terra (Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brazil)

Natasha Silva, 28 years old, lives in a favela in São Paulo, the largest city in Brazil. Mother of three, she was fired from her job as a cleaning assistant, due to COVID-19. In addition to the lack of salary, she faces another drama, the consequence of classes’ suspension is that she needs to pay for all the children’s meals (Folha de São Paulo, 03/27/2020). Luciana dos Santos, 45, also living in a favela in the same city, was already unemployed before the crisis. With the closure of schools, five of her nine children are without receiving the only balanced meal of the day. Luciana has been looking for food in supermarket dumps, without finding it (Folha de São Paulo, 10/04/2020).

Despite the crisis erupted by the COVID-19 pandemic reaching the labour market all over the planet, the examples mentioned above show us that there are some particularities. In the following lines, I intend to address the Brazilian case briefly and reflect on some effects of the crisis on the increase of inequality, such as its likely harmful impact on an already large number of unemployed and informal workers, as well as the Brazilian State’s attacks on workers’ rights.

An already precarious labour market

Brazil is a country with a long history of precarious labour relations. In 2019, therefore before the crisis caused by COVID-19, out of a population of 210 million people, the workforce was composed of 106.2 million, of whom 11.6 million were unemployed, and 4.6 million had given up looking for a job, totalling 16.2 million people. Of the employed workers, 40.9% were in the informal sector, which means that social rights did not guarantee them. Among these, it is possible to check workers without a formal employment contract, and those who worked on their own and did not contribute to Social Security.

It is essential to mention some characteristics of the Brazilian labour market. Of the employed population, 29% received up to a minimum wage per month, about 200 dollars. Gender and race have a direct impact, with black women, for example, having an unemployment rate (16.6%) that is twice that of white men (8.3%). Besides, about 20% of black women were involved in paid domestic service, and they are also the majority of the 6.3 million workers in the sector. In this, workers who have a formal contract receive 68% more than informal workers, which gives us a dimension of the impact of informality in the country.

A black domestic worker was, in fact, the first person to die of COVID-19 in the state of Rio de Janeiro, one of the most populous in Brazil. Cleonice Gonçalves, 63, worked in Leblon, an elite neighbourhood in the city when her employer returned from a trip to Italy during Carnival. While waiting for the result of the COVID-19 exams, the employer did not warn Cleonice or removed her from work. Cleonice died on March 17, the same day that her employer received a positive diagnosis (Spiegel, 04/07/2020).

In the pre-crisis scenario of the COVID-19, the labour market in Brazil was already marked by unemployment and precariousness, with a large percentage of workers who were discovered by social legislation. It is not possible to measure the impact yet. However, a study by the Universidade de São Paulo (USP) points out that eight out of ten Brazilian workers are at risk of losing their jobs or part of their income because of the present crisis (Folha de São Paulo, 18 /04/2020). Everything indicates that we will have an increase in the population living in extreme poverty, with less than 30 dollars a month, a number that in 2019 was already 9.3 million people in the country, and it is expected to become 14.7 until the end of this year (O Globo, 20/04/2020).

Attacks on labour rights

In a scenario of worsening social inequality, which is no longer small, and greater insecurity in the labour market, the ideal would be for the State to adopt policies that preserve work, but also the lives of workers. While in countries like France and Germany, the respective governments have approved measures to guarantee workers part of the reduced wages in the period of the crisis, for example, in Brazil we see the opposite, the federal government takes the time to remove even more rights from workers.

The last labour reform in Brazil came into force in 2017 and had the effect of diminishing labour rights. A direct consequence was that not only has unemployment not decreased, but informal employment relationships have also increased. Jair Bolsonaro, president since last year, has sought to increase attacks on workers’ rights further. In 2020, reform in Social Security was approved, which made it even more difficult for the population to achieve the right to retire.

President Jair Bolsonaro’s proposed the “yellow and green labour contract” (alluding to the colours of the Brazilian flag), last year, seeking a new way of hiring young people aged 18 to 29, unemployed for more than 12 months and rural workers. Among the flexibilization/withdrawals of right is the exemption of the employer to contribute to Social Security, with the exemption of charges for the bosses reaching savings of 70% in relation to a normal contract. Not being voted until the COVID-19 crisis, the proposal was approved by Congress on April 14 and is awaiting a Senate vote.

Another measure was the approval of the wage’s reduction by up to 70%, and the government must compensate part of the loss of work. It turns out that this compensation is minimal. Besides, it was approved that in most cases the cut can be made directly between boss and employee, without needing union approval, as provided for in the country’s labour legislation.

In the case of informal workers, Congress approved aid of 600 reais (about 120 dollars), for three months. To be entitled to the aid, the worker must not be receiving any other from the federal government, including Bolsa Família, an income distribution program. It means that Luciana dos Santos, mentioned at the beginning of this text, who receives 220 reais (about 40 dollars) per month from Bolsa Família is excluded from the aid.

Attacks on workers’ lives

If attacks on labour rights were not enough, what we see today in Brazil is an attack by the president on the lives of citizens. Minimizing, from the beginning, the impact of COVID-19, Bolsonaro has continuously disregarded the then minister of health’s recommendation of social isolation. The last time, it was on Sunday, when he appeared to speak in a mobilization against isolation, but whose banner was also the return to the military dictatorship.

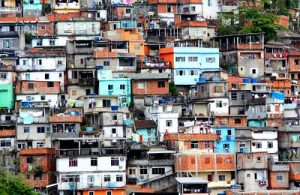

COVID-19’s cases, even underreported, already number more than 38,000, with 2,400 deaths. Several public hospitals, many filled before the crisis, no longer have ICU beds for new patients, and the country has not yet reached the peak of the disease. The challenge with prevention in Brazil becomes critical, for example, in the various favelas in the country’s cities, such as those in which Natasha and Luciana live. In addition to the high population density, many face the lack of clean water, making it impossible to provide essential primary care, which is to wash their hands continually.

Faced with the false dilemma between economy and life, Bolsonaro opted for the defence of the first. Instead of trying to guarantee the minimum conditions of survival for people like Luciana and Sheila, he has put the population at risk by encouraging an end to social distance, even in the face of the daily increase in cases and deaths. Also, his option is clearly to get support from the business community when attacking labour rights, and many of these entrepreneurs are already asking that the measures may be valid beyond the current period of trade and industry´s closure.

Not only does the fear of COVID-19 affect the Brazilian population, for a considerable part, it is also the fear of unemployment and hunger. For the country’s social movements, the challenges will be to fight for the reduction of inequality and the defence of rights, but also against constant attacks by the government of Jair Bolsonaro.

If you would like to contribute to this debate, please send your blog post to worck@worck.eu.